PONDEROSA: an artist/poet collaboration

PONDEROSA ARTIST STATEMENT

In 2015, Nancy Holmes, a poet and Associate Professor in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna invited me to collaborate with her on the topic of the ponderosa pine. Since we met in the late W.P. Kinsella’s short story writing class at the University of Calgary in 1981, our friendship has endured throughout our transitions into marriage, becoming mothers and now grandmothers. Having holidayed in the Okanagan for over 30 years, I was already familiar with the ponderosa pine but thanks to Nancy and my two artist residencies in Kelowna, I became deeply immersed in all aspects of the pinus ponderosa (the reflective pine) and its dry, rocky and fire-prone environment, heartrendingly beautiful but tough to live in. Although programmed to resist fire, this tree has been compromised by the pine beetle infestations, leaving it more vulnerable to the increasing frequency of fires, an aspect I incorporate into many of the paintings.

Our friendship and this project merged organically as we hiked, talked, shared ideas about verticality, entanglement, pathways, colour, fog/smoke and texture. Her poetry inspired me to explore new ideas and imagery, enriching not only my perception of these marvelous trees, but also my understanding of the changing climate we’re living in and the impact it’s having on us all.

Branches and Bark: An Essay on the Ponderosa Pine Paintings of Teresa Posyniak

Nancy Holmes

In a recent blog post, visual artist Jerry McLaughlin speaks of the intimate links between poetry and painting: “[b]oth offer an opportunity to discover something inside yourself that is outside everyday experience.” Discovery that moves between what is outside and what is inside beautifully describes how I, a poet, encounter my friend Teresa Posyniak’s “Ponderosa” paintings.

First the outside. The ponderosa pine is a lanky, long-needled, vanilla-resined, multi-coloured tree found growing in western North America’s dry, high altitude ecosystems. Scattered over the rain-shadow slopes of the continental divide, the ponderosa straddles the Rockies, slipping into Alberta here and there, dotting the high plateau grasslands of British Columbia and reaching far south into California and beyond. In the Okanagan Valley where I live, the tree is a defining feature—its silhouettes, its colours, its scents and its ecology bestow upon these lands a vivid sense of place. The ponderosa has relationships with the grasses at its feet and the birds and insects in its arms. Sadly, it also offers a symbol of the degradation and slow violence (to use eco-critic Rob Nixon’s phrase) of climate change as the mountain pine beetle riddles it with a million bullet holes and it is burnt at the stake in fire after fire as the West blazes up each summer. Its sensuous, dazzling, and vulnerable presence is the beginning and ending of Teresa’s paintings and my poems.

Outside touches inside when you enter the land of trees. The Japanese have a term for a walk in a forest: shinrin-yoku, a “forest bath.” The phrase expresses a walk’s refreshing potential. Such a walk can be leisurely, like a bath. You can relax, feel lighter and more buoyant. Yet different kinds of forests have distinct effects. The deciduous forests of eastern North America, for example, seem particularly suited to resting the busy mind. With their summery canopies filtering gold and green over the leaf mould floor, configurations of light and shadow sway back and forth over lush undergrowth of forked and layered shrubs and plants. The immense, tangled, fractal patterning scrubs mental states, freshens the inside of the skull, applies a dose of cool shade and luminous chlorophyll to the thoughts knotted up in there. A mind massage.

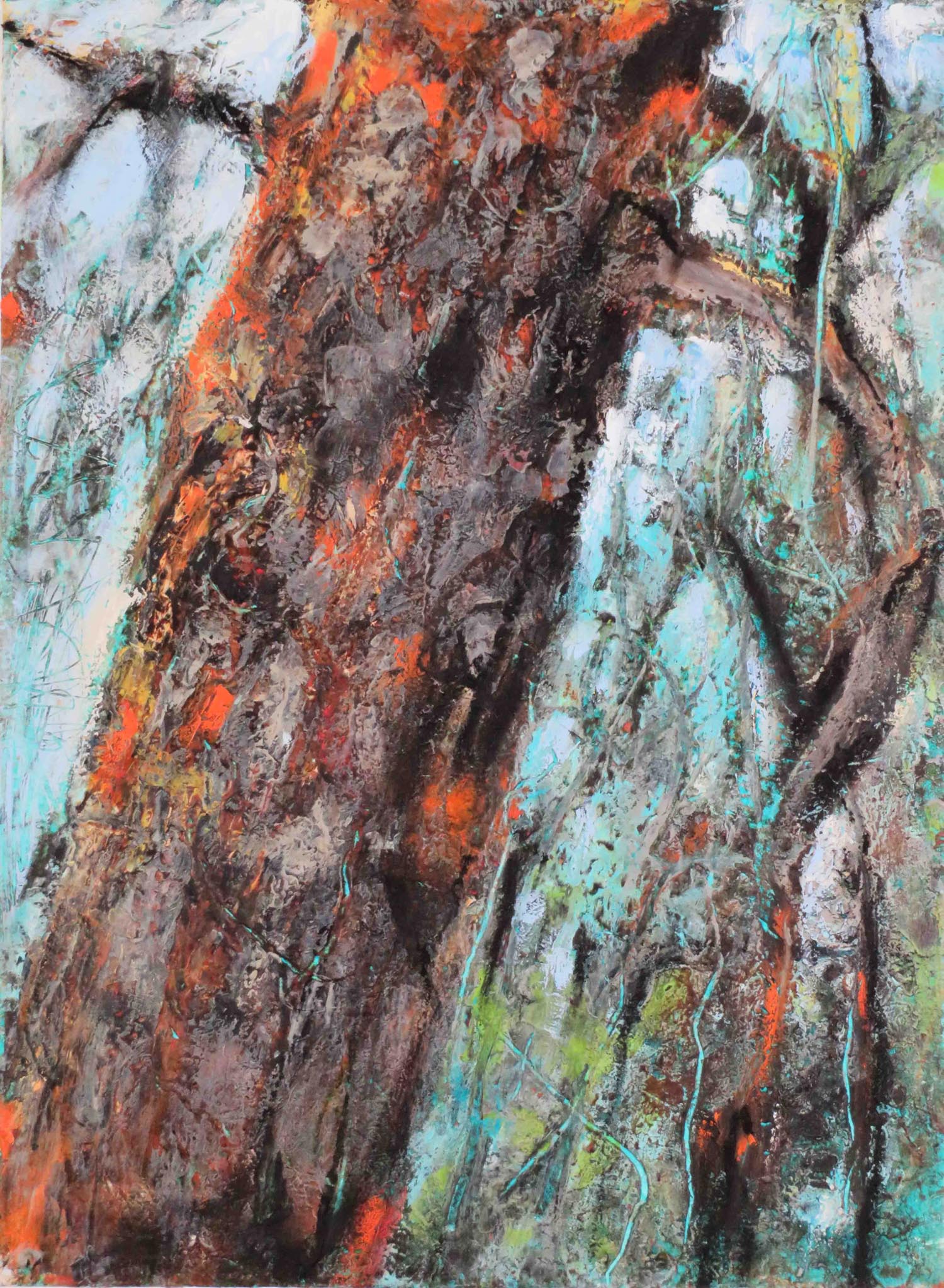

But a ponderosa forest is a different immersion. It offers something ceremonial, less a rinse than a ritual. Teresa’s paintings usher you into the aura of a spacious, sharp, and austere forest. Ponderosas tower over light-filled savannahs of prickling grasses and cacti. The forests are open and airy but full of harsh cuts and burns, often riven by canyon and cliff. The trees are wrapped in striking weather: sun-drenched and parched, or muffled in swaths of grey fog, smoke or snow. Water is sparse and green is subtle, but other colours are rich and complex: muted silvers, vivid oranges and yellows, blues and countless rusts and browns. In these great dry forests, the ponderosa’s aromatic and vivid presence offers not a massage or luscious bath but rather a soul-searching. The ponderosa speaks to whatever spiritual tatters you have left in your busy and practical life. Teresa’s paintings lead to this kind of wonder. She takes us into an experience of the ponderosa forest as akin to entering an unfolding meditation or a prayer undertaken in troubled times.

In fact, instead of resting the mind, the ponderosa forest exposes complicated pathways through our sad and sorry dualities. The wild and twisting pine branches that Teresa captures so stunningly in her paintings remind me of the anxious, scarring digressions and ruts of our mind. But these branches are vibrating and distracting from a mystery: they veil the inner core of being—the scented cathedral column of the trunk crusted in its stained-glass bark.

The branches are blackened, smoke-webbed, clamorous, trying to get us to hear and see something, possibly something dangerous. The branches call out in a tangled language—they are tortured gestures, texts embodied and crying out. They are telling us dark things. There is urgency in these branch paintings—they are restless fingers, wires, all those springy electric and zapping things that connect and crawl (hair standing on end, hair enhancing touch). They are sketches of aliveness even as they shrivel and become skeletal. The branches are half-dead and half-alive like hair, like electric wires, like our everyday selves, like our language, like our relationship to nature.

But the branches are only part of the experience. In Teresa’s paintings, space is always shimmering below the surface. The trees are layered in light and texture. There is depth. The branches may be electric, synaptic, black and burdened, but beneath them is a core of stillness. The long joints and fissures of the bark glow and spark. A quiet being resides beneath the frenzied branches: the trunk, a closed and jewelled casket. We are invited to contemplate what is deep inside. Encased in dazzling bark is the living trunk of the tree. The crusted bark encloses the beetle-eaten holiness at the centre of everything.

In the paintings, sometimes we glimpse the trunk with its shards of orange through a branchy veil. Sometimes we see the bark directly in front of us, thick, contained, and peaceful with its flashes of coloured joy. Often we see only a portion of the trunk, one pared slice. The tree’s immensity seems too great to take in all at once. And here at the centre of the tree, we are at the heart of a kind of terror. The bark is quiet, full of equanimity, even as the language of the branches mimics the killing tracks of the pine beetle that burrows invisibly into the trunk of the tree. The paintings call up the yearning we have for a cosmic connection yet they are true to how rarely and how partially we stay in such moments.

That centre of being, troubled and luminous and wordless, is what I bump up against as I look and look at Teresa’s paintings. Like spiritual practices, these paintings are about encounter, about really seeing through the noise of everyday life. This looking becomes the doorway into my own poetry. The writerly quality of these paintings pulls me in. The pine branches scrawl obsessively on the sky and on the bark, often bitterly or angrily, mirroring the inky tracks of the pine beetle’s corrosive journey into the brilliant trunk of the tree. The trunk and bark paintings seem to emanate the pine’s particular incense and resins, as well as heft and hum that give the core of the tree a sacramental weight, like a great medieval book. My poems began to multiply and divide along the lines of spiritual inwardness on the one hand (the bark and trunk) and, on the other, mental toxins and angry accusations (the branches.) In my bark poems, I am being schooled in and reminded of something I should know about nature and our relationship to it. In my branch poems, I let loose social and cultural noise full of blame, ego, anger, paranoia, all the dissonance that gets in the way of our being fully conscious human beings aware of and grateful for our dependence on this earth. I think my poems respond to something in the paintings about our own human-created crisis at the heart of the ponderosa’s imperilled beauty.

Teresa’s paintings are witnesses of the mysterious nature of trees which we now know are complex, communicating, and sensitive beings essential to life on earth. The paintings of these remarkable trees can summon awareness of our own inner being. They remind us of the opaqueness of nature, how obdurate we are and how unknowable nature is. As they are crusted, so our eyes and hearts are crusted over. Yet, these paintings cause cracks to appear. As we experience the paintings, it is possible to feel not only the wonder of this tree species but also the pain of our own minds and souls in a life and death struggle between calamity and hope. Teresa Posyniak helps us see the ponderosas and ourselves as sacred beings caught in webs of unconsciousness and dysfunction. Walking amongst her paintings is like a ponderosa forest bath: a cleanse and a lesson, a benediction and a warning.

NANCY HOLMES has published five collections of poetry, most recently The Flicker Tree: Okanagan Poems. She is the editor of Open Wide a Wilderness: Canadian Nature Poems. She is Associate Professor in Creative Writing at The University of British Columbia in Kelowna, British Columbia. She also collaborates on eco art projects, most recently around about native pollinators in a initiative called Border Free Bees borderfreebees.com. Nancy won the 2015 Robert Kroetsch National Teaching Award in Creative Writing for her innovative student project, Dig Your Neighbourhood and she is working on a new book of poetry that will include a sequence of ponderosa pine poems. nancyholmes.ca